Enjoy the Disruption

Month

Running a startup is difficult enough. Being a foreigner doing a startup is about 100x as difficult. The last thing you want to be worrying about is your Visa and not having a passport to do business.

I’ve lived in the UK for nearly four years now on a Tier 1 Visa. I moved here from San Francisco to join Mendeley as Head of R&D [note: left to found PeerJ before Elsevier moved in to buy them :)].

Last August I needed to send my Visa in for a two year extension. It has now been five months, and I still have not received my passport and new Visa. This is not an uncommon thing these days (read any Visa forum) for the UK Border Agency, the agency in charge of immigration decisions.

Obviously being without your passport is rather hampering as a co-founder of an Open Access tech/publishing startup with locations in both London and San Francisco. It’s outrageous actually, and the UKBA knows exactly what my business is.

I know for certain that I am not the only entrepreneur going through this. A shame, as startup companies are the ones bringing new investment to the UK economy and creating new jobs. And with the RCUK pushing for Open Access, you’d think there would be added incentive in this case. David Cameron is full of a lot of hot air, professing to be on the side of foreign entrepreneurs. From where I sit, we’ve received no help.

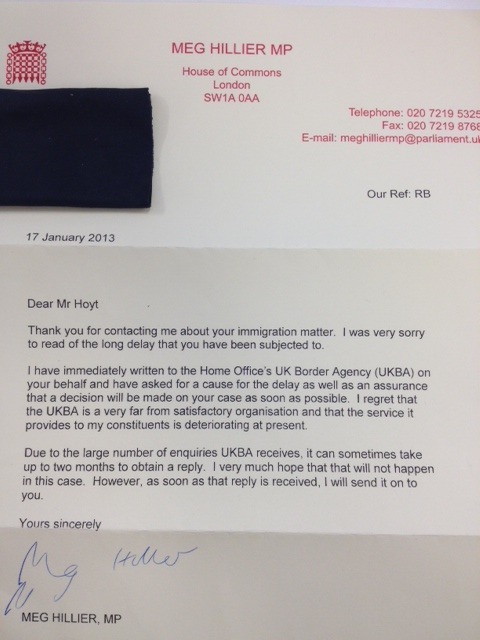

Finally, this week I decided to do something besides futile attempts at contacting the UKBA for information on the delay. I wrote to my local MP, labour party member Meg Hillier. And behold, a written reply within two days of my emailing.

“… I have immediately written to the Home Office’s UK Border Agency (UKBA) on your behalf and have asked for a cause for the delay as well as an assurance that a decision will be made on your case as soon as possible. I regret that the UKBA is a very far from satisfactory organisation and that the service it provides to my constituents is deteriorating at present. …”

- Meg Hillier MP - 17 January 2013, private correspondance (see image in this post)

Thank you Ms. Hillier.

Probably the most disturbing thing to me about the Aaron Swartz tragedy is this statement in 2011 from US Attorney Carmen Ortiz:

“Stealing is stealing whether you use a computer command or a crowbar, and whether you take documents, data or dollars.”

That is teaching our children that the law is always correct and that discretion should not be used when enforcing the law. It’s teaching our children not to question what they are being told by those in power. Had the American fore-fathers believed that “treason is treason” then the United States would have never had its Revolution and founding.

There is no physical law that governs the Universe that outlines stealing, killing, lying, etc. These are human fabrications to govern us as a society, tribe, and culture. We equally have the capacity to dictate when stealing isn’t stealing, or when an act of treason is the right thing to do as the American fore-founders discovered. That is how we advance as a civilization.

There is a tremendous difference between stealing for personal gain, and “stealing” [1] to release academic papers paid for with tax-payer money. A true leader would recognize that. It’s been reported that Carmen Ortiz had political ambitions to one day run as Governor of Massachusetts. Is that the kind of leader a state would want? A false leader who doesn’t recognize when an act has morally justified grounds? A real leader would act to make changes, not throw the book at someone.

MIT should be ashamed as well, whether they were actively pressing charges or passively standing by [reports are conflicted over this]. MIT as well is supposed to be leading us. In the past they were one of the first universities to offer free and open classroom lessons online. Here, they failed miserably to lead by example that academic research should be made open.

The Aaron Swartz story is bigger than just a 26 year-old doing some computer hijinks and getting bent-over by those in a position of power. It’s even bigger than the importance of Open Access to academic research. It’s surfacing some major issues that we have in society in both the U.S. and beyond about true leadership [note: I am a US citizen currently residing in London, UK]. Ortiz was put into a position to use her discretion. Instead, she let her ambitions dictate Aaron’s fate.

At the end of the day, if it is against the law to steal whether morally motivated or not, then you’ve broken the law. Laws can be changed though. New countries can be formed. And leaders in power can use their discretion to apply fair judgment, not to further their own ambitions. Where have all the true leaders gone?

footnote

1. Note that Aaron wasn’t even technically stealing in terms of the law, at most it was breach of contract [according to several reports].

This morning, by way of @SimonBayly, I came across the article “Towards fairer capitalism: let’s burst the 1% bubble” in yesterday’s Guardian.

There’s a nice late 1800s/early 1900s quote that I can’t help but correlate with today’s academic publishers:

“The barbarous gold barons do not find the gold, they do not mine the gold, they do not mill the gold, but by some weird alchemy all the gold belongs to them.”

- Haywood, William D. The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood. New York: International Publishers, 1929, p. 171

What this is saying, and the thesis of the Guardian article, is that the gold barons of the 19th Century and the financial bankers of the 21st century are wealth extractors, rather than wealth creators.

The Guardian thesis goes on:

Value creation is about reinvesting profits into areas that create new goods and services, and allow existing goods to be produced with higher quality and lower cost.

Think about that. When was the last time we saw academic journals lower their prices? Subscription-based (and in cases even Open Access based) academic publishing is the opposite of value creation, it is value extraction.

The byproduct of innovation of the Internet has turned a wealth creating industry of academic publishing into a wealth extracting one. Make no mistake, today’s publishing executives are equal to yesterday’s gold barons and hedge fund managers. The Internet has given publishers the opportunity to lower prices, but they’ve chosen to do the opposite. That’s value extracted from scientists.

An important aspect of the Guardian thesis on economics isn’t that profits are inherently bad, but that they need to be reinvested to create more value.

I’d like to think this is what we are trying to do at PeerJ by creating value for the community. We made the price ridiculous at $99 for lifetime publishing. You’re forced to innovate with a price tag like $99. What’s more, we’re experimenting with free publishing as well with PrePrints (non peer-reviewed and non-typeset academic articles).

The thing is, we don’t know what the right price is for academic publishing today [1]. I don’t think it is what subscription journals have been charging, or most Open Access journals have been charging for that matter either. I suppose the thesis, of hedge fund managers and academic publishers robbing value, shall be proven if PeerJ continues to survive.

If you’re not lowering your prices then you’re not innovating. And if you’re not innovating, then you’re not creating value.

Footnotes:

1. It’s definitely not free, as it costs money to run servers and pay staff who maintain those servers, etc. ArXiv (non peer-reviewed) is a good example of what the right price might be, though even they have substantial costs that need support.

If it weren’t for Aaron’s heroic actions to release academic research articles in 2011, I am unsure if PeerJ would have ever been born.

Today’s news was shocking. Aaron Swartz was found dead from apparent suicide on the 11th of January, 2013 at the age of just 26. For the science community and Open Access advocates, Aaron was the man responsible for the (near) liberation of all pay-walled JSTOR content in mid 2011. He also co-wrote the first RSS 1.0 specification at the age of 14 and led the early development of Reddit.

JSTOR and MIT eventually dropped the civil case against him (publicly anyway), but the U.S. government continued criminal proceedings against him. JSTOR, it should be noted, was not his first attempt at freeing information. Aaron was facing up to 35 years in prison for the act of setting academic research free. It’s unknown if this was the reason for his suicide, but that’s not why I am writing.

The events around JSTOR and Aaron’s prosecution were probably the final straw for me. What kind of world do we live in, where such harsh punishment is sought for liberators of publicly funded information? The indictment of Aaron and the severity of the probable punishment angered me.

I wrote the following in July 2011 after learning about Aaron’s fate:

Will the JSTOR/PirateBay news be Academic Publishing’s Napster moment? i.e. end of the paywall era in favor of new biz models?

Something had to be done. I wanted to turn Aaron’s technically illegal, but moral, act into something that could not be so easily thwarted by incumbent publishers, agendas or governments. Over the next few months I let that desire build up inside, until one day the answer came in the Fall of 2011.

It was then that the groundwork for PeerJ was first laid; a new way to cheaply publish primary academic research and let others read it for free. Aaron was significantly responsible for inspiring the birth of PeerJ and what I do now trying to make research freely available to anyone who wants it.

I hope that when the history books are written in decades time, that Open Access crusaders like Aaron will still be remembered. My thoughts go out to Aaron’s friends and family. Know that Aaron’s light and efforts will live on. Thank you, Aaron, for inspiring us.

Good discussion going on over at Ross Mounce’s blog on which publishers are using XMP and why it is a good thing.

How often do we hear this, “We’ve just raised a small seed round and are using it see if we can gain product-market fit.”? In other words, they’re spending time and money without any inclination that there is a market available. I’ve not done the research, but at what point in history did this become a good strategy for the founders involved? The odds of success are tiny.

Building a startup with a huge market available to it is hard enough. Building a startup and trying to create its own market is a disaster waiting to happen. Far too often, I see startups trying to do the latter. You are wasting your time if you don’t start with an idea that has product-market fit from day one.

I’ve often heard people say that Apple created an entirely new market when it introduced the iPad. Same with the iPhone when the app store was launched. This isn’t true though. The ‘market’ already existed, it was the media/entertainment market. The iPad was just another device to leverage that market. Apple knew what it was doing.

I mention Apple, because they are a good example, for this specific case, in knowing your product-market fit before you even begin. For startup companies that manage to raise a small seed round (<$500K) it means you’ve been given a chance to demonstrate that product-market fit. For the Angel(s) involved, that’s great if you go on to prove that, and if not, well, they’ve invested in enough startups to hedge their losses. For >95% of startups though, you will never achieve that product-market fit if you don’t already have it from the start.

The best way to tell if your idea/startup has product-market fit is to ask yourself what other companies are successful and doing what you are thinking of doing. By success, I don’t mean raised a round (or even multiple rounds), I mean profitable and a staple in a large portion of people’s lives. If you can’t name several companies in your area, then 1) you don’t have enough knowledge of your area or 2) your idea doesn’t have an audience.