Enjoy the Disruption

Month

I’ve read two seemingly diametrically opposed startup retrospectives this week. Really, same goes for every week.

The first was a post-mortem of a startup failure that tried making customized and crowd-sourced designer jeans.

The second was a lesson on getting turned down by VCs from Justin Kan, founder of Twitch, which lets people watch others playing video games.

In the first instance, the moral of the story as told by the founder is to do your homework, i.e. market research and validation before starting the business full-on and wasting six years of your life.

In the second instance, Twitch, the moral of the story is to not listen to anyone who thinks your idea is crazy and persevere through it. Show the world!

Here’s what these two blog posts (and similar) usually forget to mention…

Both of those bits of advice are wrong and correct. Sometimes you can’t validate an idea ahead of time. Other times you can validate market potential, but the data may tell you to quit, when actually it could very well succeed. Or it could be the opposite, the market says yes this is a winner, and it turns out not to be.

So what the hell is one to do then?!

Really, there’s only one thing you can do - if your idea is uncertain and you decide to follow through with it, then become comfortable with that uncertainty. If you don’t have that risk appetite, then head the other direction and look for an idea with more certainty in the market (which will have different barriers of course).

Not every good idea is worth advancing, and not every crazy idea should be dropped. The forgotten piece of advice is that you need to ask yourself how much risk you’re willing to take on board. And that’s unique to everyone.

Even for the seasoned and experienced, that can be a difficult question to honestly answer. So, look for parallels in your life where you were possibly biting off more than you could chew, its outcome, and how you felt about it. Validating your appetite for risk is probably the most important element to starting something. There’s risk in any business venture.

Just spotted this as Slack has recently updated their API Terms of Service, though it may have been in there before this update?

Of course, faced with either jail time courtesy of the government or breaking Slack’s TOS, which do you think a developer would choose? Slack legal time just covering their arse with this clause.

https://slack.com/terms-of-service/api

9.1 Government Access: You will not knowingly allow or assist any government entities, law enforcement, or other organizations to conduct surveillance or obtain data using your access to the Slack API in order to avoid serving legal process directly on Slack. Any such use by you for law enforcement purposes is a breach of this API TOS.

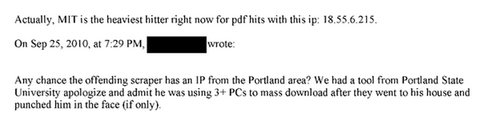

Courtesy of JSTOR. Well, hopefully not JSTOR as an organization, but at least one of their employees thinks you should get knocked out. That was just learned from a Freedom of Information Act request obtained from the Aaron Swartz saga. You can view all of the files obtained from the FBI, Secret Service, MIT, JSTOR, US Attorney’s Office and others at swartzfiles.com

The above is from page 4 of more than 3K pages of internal emails from ITHAKA.org, which is the non-profit responsible for the JSTOR digital library (whose mission is “to foster widespread access to the world’s body of scholarly knowledge”). It’s a couple of systems administrators communicating in the context of high download activity going on at MIT (which we later learn was Aaron Swartz downloading academic papers).

Sadly, despite its mission, JSTOR believes it is no longer capable of sustaining itself in the digital era without resorting to restricting access to knowledge. The Internet and World Wide Web, designed to spread information, have changed everything, sometimes ironically.

For its part, JSTOR settled a civil suit with Aaron Swartz out of court, and later told the US Attorney’s office in Massachusetts that it no longer had an interest in further proceedings. The US Gov’t didn’t stop, however.

Getting punched in the face was the least of Aaron’s worries. The FBI had much worse in mind for him (and succeeded in doing) for the act of downloading PDFs. It culminated in the unnecessary loss of his life.

There’s too much in the FOIA for any one person to really go through entirely, but have a perusal of the documents and let’s remember what Aaron stood for, and that we can do better when it comes to being stewards of the world’s academic knowledge. As I’ve stated before on this blog, without Aaron there may have never been the motivation to start the journal PeerJ. News of Aaron in 2011 was the catalyst to finally say, “Nothing about the outrageous costs in publishing is changing. What can I do?” Thankfully Pete Binfield agreed with me and we set out to make public access to research faster, cheaper to produce, and most importantly free to download. No one deserves a punch in the face for pursuing academic knowledge.

What is CHORUS and why is it important to know about if you’re an academic? From the FAQ (bold emphasis mine):

CHORUS (Clearinghouse for the Open Research of the United States) is a not-for-profit public-private partnership to provide public access to the peer-reviewed publications that report on federally funded research. Conceived by publishers as a public access solution for funding agencies, research institutions, and the public, CHORUS is in active development with more than 100 signatories (and growing). Five goals drive CHORUS’ functionality: identification, discovery, access, preservation, and compliance. CHORUS is an information bridge, supporting agency search portals and enabling users to easily find free, public access journal articles on publisher platforms.

Only it fails in the one thing that it claims to support, public access - at least as far as I can tell so far. And this is the big worry we’ve had all along, that a paywall publisher backed solution to the White House’s OSTP mandate would not work. For a critical overview of the concerns see Michael Eisen’s comments from one year ago when CHORUS was announced.

Why isn’t CHORUS working?

Let us jump right into doing a search. Here’s an example query for NIH funded research. When I ran this search today (August 1, 2014) I got only 3,775 results. Hmmm. That can’t be right, can it? Only 3,775 NIH funded articles? Moving on…

The first result I got was to an article published July 2014 in the American Journal of Medical Genetics. Click the DOI expecting public access, and I hit a paywall. Oh wait, that’s right - CHORUS also indexes embargoed research set to actually be public open access in 12-24+ months. Next several search results - same paywall. Not until the fifth result do I reach an Open Access article.

OK fine. Perhaps it is reasonable to include a mix of embargoed papers with public open access papers - even though OPEN RESEARCH is in the name of CHORUS. I’ll just click the filter for actual public open access papers and see my results. Hmm, unfortunately there is no filter for actual public open access papers. Ruh-rohs.

And there does not appear to be any labeling on search results indicating whether a paper is actually public open access or still embargoed (for some unknown period of 1-2 years). Ruh-rohs again.

Are we just seeing teething pains here? In some things for sure, for example only having 3,775 NIH results (when there are millions). It can take time to get all of that backlog from publishers (though I don’t know why they’d launch with such a paltry number). However, I don’t believe the lack of Open Access labels or ability to search only for papers already Open Access (rather than embargoed) is a teething problem. That’s a major oversight and makes you wonder why it was left out in a system designed by a consortium of paywall publishers. I can’t imagine SPARC, for example, leaving out an Open Access filter if they had built this search.

What else is wrong with CHORUS?

The above was just one technical problem, albeit a very concerning one. The main issue is the inherent conflict of interest that exists in allowing subscription publishers the ability to control a major research portal. As Michael Eisen put it, that’s like allowing the NRA to be in charge of background checks and the gun permit database.

In the title I asked, “how does CHROUS stack up to PubMed?” We need to make this comparison since one of the aims of CHORUS is to direct readers to the journal website, instead of reading/downloading from PubMed Central (PMC).

Perhaps most importantly, CHORUS allows publishers to retain reader traffic on their own journal sites, rather than sending the reader to a third party repository.

And if you believe Scholarly Kitchen then PMC is robbing advertising revenues from publishers and PMC is costing taxpayers money as a useless redundant index of actual public/open access papers. Let’s not mince words, Scholarly Kitchen (and by extension the Society for Scholarly Publishing) believes that PubMed and PMC should be shut down. No one believes taxpayer money should be needlessly wasted, but it is a tall order to replace PubMed and PMC, so our expectations for CHORUS should be just as high.

Unfortunately, it is clear from using the CHORUS search tool that I have far less access and insight into publicly available research. And while an open API is slated for the future, it is questionable whether it will be as feature rich as NCBI’s own API into PubMed and PMC.

CHORUS also fragments an otherwise aggregated index with PubMed. CHORUS looks to index only US-based federally funded research that is either Open Access or slated to be after a lengthy embargo. This means you still need to rely on PMC to find a non-US funded Open Access article. Clearly we still want that since it helps US researchers, right? Then why shut PMC down?

CHORUS isn’t free either. They’ve set the business model up such that publishers pay to have their articles indexed there. Do you think publishers are going to absorb those costs, or pass it along to authors/subscribers? The fact that CHORUS won’t index unless a publisher pays is rather scary; especially if CHORUS were to ever become the defacto database for finding research.

In Summary

I think CHORUS will improve over time, for sure. My worries though are the inherent conflicts of interest and that a major mouthpiece for CHORUS is calling for the removal of PubMed and PMC. I’m also skeptical whenever I see an organization using deceptive acronyms. CHORUS is not a database of Open Research as its name suggests. At least not ‘Open’ in the sense that the US public thinks of open.

You see, if CHORUS can convince the public and US Congress or OSTP that research under a two year embargo is still 'open’ then they’ve won. It’s a setback for what is really Open Access. Nothing short of marketing genius (or manufactured consent) to insert Open Research into the organizational name.

I think these are legitimate concerns that researchers and the OSTP should be asking of CHORUS.

So Brendan Eich has resigned as CEO from Mozilla. From the words of Mozilla Executive Chairwoman Mitchell Baker, this wasn’t a result of his past donation to Proposition 8 in California banning gay marriage, but rather “It’s clear that Brendan cannot lead Mozilla in this setting…The ability to lead — particularly for the CEO — is fundamental to the role and that is not possible here.” i.e. the controversy that this brewed was tarnishing Mozilla’s reputation, trust, brand, etc.

Unfortunately, this is one of those situations where no one ends up feeling happy. This got ugly on both sides. It is sad that the co-founder of Mozilla and the creator of javascript had to resign. It sucks, I’m sure most of us had high hopes. At the same time Mozilla was being led by someone who wouldn’t apologize for wanting to ban gay marriage, so people had every right to voice disagreement over that promotion.

Now however, there is a lingering “meta” controversy over whether the way this was handled on both sides was wrong or right. Was the “anti-Eich” crowd too vengeful, too close to being what has been described as being a lynch mob, were they being hypocritical and intolerant? Were the folks supporting Eich being insensitive to a growing civil rights movement, misunderstanding what Mozilla represents, erroneously mixing a specific case with a hypothetical slippery slope?

In the larger picture, these questions and issues exposed during the controversy are just one more signal that “tech” still has much growing up to do. On the one hand tech is dominating every industry and part of our lives. “Software is eating the world,” a quote from Marc Andreessen, which is often used to describe what is going on. And tech is still in its infancy or teenage years in terms of how long it has been with us, which brings challenges as it inundates our culture and organizational behavior practices. Tech is even influencing our politics now, as seen with Twitter in various countries, and the SOPA movement. Some say the tech community went too far with SOPA when websites blacked themselves out in protest, and of course the sexism that continually rears its head in tech is immaturity at its best.

When you have something that is massively influencing every part of our lives, but is still immature, then it can only lead to more “meta” controversies like the Mozilla one. We (i.e. the community, public) simply just don’t know how to appropriately react yet to these situations, it’s going to take time to adjust to what tech in our lives means. Although I think most calling for Eich’s resignation were proportionate in their response, their were outliers who went too far in how they handled it. There will always be people who go too far of course, but now tech can ignite these crowds in a blink of an eye and carry people with it who would not normally participate. That said, I’m confident that as we grow to understand what tech means in our lives that we will resolve that issue in time.

I think we would all be served well if a post-mortem was done for this particular controversy. And this increasingly common situation of how “tech reacts” deserves to be studied as a larger whole. There is an awful lot that we could learn about ourselves and tech in our lives. Important as tech and its social impact isn’t going away, it will only increase.

A new exclusive interview with anti-LGBT supporter Brendan Eich on CNET shows that the controversy is not dying down. My own thoughts on why this is a bad choice as CEO for Mozilla Foundation were posted a few days ago. Since then, we’ve seen three board members step down in conflicting reports stating they resigned in a form of protest, contrasting with Eich in the CNET interview and the remaining board stating they were long planned for.

Needless to say, things are very foggy over at Mozilla and the future is still unclear. One thing is clear, however, that the leadership (CEO and Board) in fact is incapable of leading. Even if they now decide to fire Eich and replace him with a more forward-thinking CEO, it will be only because they’ve caved after sitting back for weeks to measure public opinion; that’s playing politics rather than leading. The Mozilla board I’d like to see is one that knows what the right thing to do is from the get-go or decisively changes course if a mistake is made. What this controversy has revealed is that Mozilla plays politics, it doesn’t lead. That paints a picture where the future at Mozilla will inevitably be filled with more mistakes.

Mozilla doesn’t share my values - both in terms of installing a CEO who doesn’t support LGBT rights and in it’s overall leadership characteristics. It’s disappointing. I’d like to see the remaining board resign and I won’t be returning to any Mozilla products until that happens.

I just don’t understand WTF the Mozilla Foundation was thinking on this one. It’s akin to making someone a CEO who donated to segregation campaigns in the 1960s. You just wouldn’t do that.

Gay rights have not yet achieved the same acceptance as other civil rights have, but they will do so undoubtedly one day. And when that day arrives, and it already has in most of Mozilla’s fan base markets, it is going to haunt the Mozilla Foundation even more than the decision today is doing. Mozilla looks to the future in all it does, except when it comes to its leadership apparently. The future profile of CEOs will not have anti-LGBT beliefs, and Mozilla needs to be skating to where the puck is going, not where it’s been.

What is really troubling is that the origins of the tech industry, the West Coast tech, were about tolerance and civil rights. Personal computers and related technologies were about freedom from oppression. For a tech non-profit to install an anti-LGBT CEO is completely 180 from why and how tech evolved from its early days. Technology isn’t just about what you do, it’s also about who does it. They go hand in hand.

If this was simply an oversight that was missed in due diligence of the CEO’s past then OK, but make the change happen.

With Google announcing massive price drops (https://developers.google.com/storage/) it has a lot of developers and tech managers re-thinking the use of AWS, Rackspace, etc. Certainly the $.026/GB of monthly storage and lowered compute engine prices make stiff competition. I am not convinced yet, however.

First, depending on what one is trying to accomplish, the new bandwidth prices announced by Google are still more expensive than AWS once you reach a certain volume. For heavy bandwidth out users then, it may not make sense to use Google over AWS if pricing is your only concern.

A larger issue is one of trust, and opinion shows many developers and decision makers are in agreement with me on this one. Google has failed users and developers countless times as it has pulled its APIs and services. Google has a one year notification term for its cloud computing services, but that can change, and one year is possibly not enough time if your entire business is structured around the service. The fine details of the cloud computing terms of use with Google could also give one pause compared to AWS.

Further, AWS revenue accounts for ~7% of Amazon’s overall business revenue. In comparison, the Google cloud computing business brought in roughly 1.5% of Google’s overall 2013 revenue. That alone is enough to give me a second thought when considering trusting my business or computing needs with Google due to its lengthy history of pulling services.

There are of course other reasons to distrust Google, which I won’t go into now.

AWS is likely to follow Google and continue dropping its prices as well. So, any prudent decision-makers should take a wait-and-see approach before jumping ship. And even then make a careful analysis (including future growth scenarios) of how your business or process actually utilizes the various cloud services to determine the real and future costs involved.

The Frontiers in Innovation, Research, Science and Technology (FIRST) Act (link) is doublespeak for “we’re actually going to limit Open Access.”

The FIRST Act is yet another bill that is winding its way through the US Congress that despite making claims FOR science will actually reduce the availability of Open Access. Luckily the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC) has clarified the damage that this bill would actually do to scientific advancement within the U.S. PLOS has done another writeup of the severe consequences this bill would bring.

In the past similar bills such as the RWA "Research Works Act" backed by the Association of American Publishers and many paywall publishers have used this doublespeak. The Clearinghouse for the Open Research of the United States (CHORUS), a publisher backed proposal, is another initiative filled with doublespeak, with the real aim to control access - not open it up. And more recently the “Access to Research” initiative from publishers does the opposite of what its title proclaims. It limits access to research in the digital age by adding a physical barrier and forcing you to travel hundreds of miles to a participating library instead of providing access in the convenience of your lab or home.

What really fascinates me, however, is the continued use of marketing doublespeak in these legacy publisher proposals to manufacture consent and distort the facts for financial gain. That they are pronounced with a straight face each time makes me just a little sick inside that people like this actually exist. The opposite of heroes, value creators, and leaders. If you haven’t noticed, these tactics grind my gears to the point of evoking a visceral emotional response.

Now I’ve looked to see who outside Congress is backing the FIRST Act by way of either public support or Congressional campaign donations and have yet to find a connection to the usual suspect publishers or associations. Please leave a comment if you do find a connection.

Update

As Björn Brembs points out, a number of paywall journals and publishers have donated to the Congressmen responsible for bringing the FIRST Act to the House of Reps. This is more than a smoking gun leading back to Elsevier, and a few other large publishers known for backing previous anti-OA bills.

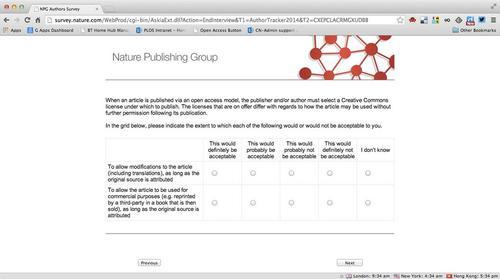

Thanks to this tweet by @CameronNeylon we see a very loaded question about Open Access licensing consequences from NPG. I should say also that there are a few other misleading questions from this NPG survey - which look to be as much as propaganda as (poorly designed) survey material.

This seems to be the new scare tactic for anti-OA activists. Explain one possible commercial use case, one likely to offend or upset academics, while neglecting to state the many other reasons one would want to allow commercial re-use: teaching in academic situations (if the academic is paid that’s commercial use), text/data mining for new cures, in certain cases physician’s may hesitate to use or cite the research after developing new tools based on that information, etc.

Maybe you have a moral reason to not want a biopharma giant to profit off of your Open Access article. Fine, fair enough, but that actually doesn’t prevent them from using the information - facts can’t be copyrighted. More often than not, the use of a Non-Commercial OA license (e.g. CC-BY-NC) has the opposite effect from what the author hoped to achieve. Peter Murray Rust explains this in an excellent writeup here. An NC license doesn’t prevent the publisher you use from profiting off of the material, it won’t stop pharmaceutical companies, but it does deter others with many legitimate use cases.

Had all software development in the early days of the 60s, 70s, and 80s restricted commercial use then we wouldn’t be here today discussing this. Open licensing with explicit reuse for commercial interests has been the foundation of software that powers a majority of the world’s websites, and software that powers research activity in academic institutions. The parallels with Open Access articles and the early days of open sourced software are massive.

For sure, all academics should be aware of the possible uses of their research, but the point is to make them fully aware of all use cases, not just a select few intended to scare. And we also need to understand that choosing a restrictive NC license may have unintended consequences as well.

Updated to add: Many, including the Budapest Open Access initiative, do not consider OA licenses with an NC clause to actually be Open Access. I agree with this position.

Whoa. Some serious debate flying around after the newly minted Nobel Laureate and Editor-in-Chief of eLife wrote that journals like Nature, Cell, and Science are damaging science.

On one side you find the supporters, such as co-founder of PLOS and UC Berkeley Professor Mike Eisen, who hopes Randy’s actions can inspire others. In the other corner are the haters shouting hypocrisy.

The way I see it, Randy had two options:

1. Say/do nothing at all, and thus inspire no one to take action.

2. Do what he did.

I’m on Randy’s side here. If we’re going to start making the changes that are needed within academia then someone must speak up, even it comes laden with ad hominem attacks of hypocrisy and conflicts of interest. And note my own COI as a co-founder of the Open Access journal PeerJ.

Let’s examine the fallacies of the naysayers’ arguments:

1. Sheckman’s words ring hollow because eLife, like CNS (Cell, Nature, Science), has a high rejection rate, even though it is Open Access. As editor-in-chief of eLife he has a conflict of interest and should not make such statements.

This argument is ignoring the actual message and its possible impact. Whether eLife is a luxury journal or not doesn’t change the message being told. Same with the conflict of interest. Those are all separate issues from the message and how people can act on it.

Additionally, it’s naive to think that everyone boycotting CNS would all of a sudden 1) start publishing with eLife and 2) that other publishing options (PeerJ, PLOS, small society journals, F1000Research, preprints, etc) wouldn’t grow.

2. Even if everyone boycotts CNS, it won’t change things because the next three highest impact factor journals will replace them.

This is a non sequitur argument and the silliest one of all. It ignores the fact that if CNS actually did go out of business, then Sheckman’s words will have achieved an f'ignly astounding result. Do these naysayers actually believe if everyone boycotted CNS that it wouldn’t have other knock-on effects within the overall academic debate on impact factor?

What would really happen if everyone were to boycott CNS is that our funding bodies, governments, academic departments, etc would take notice. It will have meant that academics’ habits have actually changed. That will lead to other changes. It won’t just lead to the next three journals replacing CNS; that conclusion is unsupported as can be.

3. Sheckman can only say boycott CNS now that he has secured his Nobel prize after publishing more than 40 times in those journals. Younger scientists don’t have that option.

This is an ad hominem argument. Again, whether Sheckman is being a hypocrite or not has no bearing on the message that things must change in order to improve scientific research. Whether younger scientists have the luxuries that Sheckman has now or not has no bearing on the message. The message is “things must change.”

That we’re now debating the merits of Sheckman’s call means what he said is already having an impact. And let’s remember that most hearing his message are not academics, but the public who are unaware of the issues at hand, but still have the power to change things through their elected officials.

If a Nobel Laureate isn’t allowed to state these things, then who is allowed? Reality is that everyone’s allowed, but not everyone has the voice that Randy now has. He can choose to remain silent, or he can try to have an impact that perhaps may help eLife, but will undoubtedly help advance science and other publishing experiments that are sorely needed. A rising tide raises all ships.

Finally, whether his words will have any real results at the end of the day or not isn’t a reason to stay silent. When we’re trying to push the boundaries we go into action knowing full well that failure is a possibility. If success were guaranteed then we’d have no need for inspiration.

Kudos to Randy Sheckman for having the courage to do what he did, despite knowing the heat he’d take. That makes him more worthy of the Nobel than ever.

This from the Guardian discussion how the new iOS7 animations are literally making people ill. And the Hacker news discussion. And I tend to agree.

Last year it was the iOS6 maps disaster (still one really).

All in all, the design choices post-Jobs have been terrible. It’s as if Apple has stopped doing user testing prior to release (if they ever bothered with Jobs).

This is Apple (and possibly Jony Ive) - fail.

I returned yesterday from Birmingham, UK and the 2013 ALPSP international conference. It was great to listen, to present, and of course nice that PeerJ won an award for its publishing innovation (we’ll do a proper post about that on the PeerJ blog shortly).

I spent some time talking with different society publishers and staff. This was new for me. My co-founder at PeerJ is much more seasoned in the publishing world than me - I’m the outsider coming from more of a quasi tech/academia/academic software background. Thus, my perspective on the current situation facing publishing is probably refreshing, naive, flat out wrong in some areas, but dead right in other areas. Yes, I’m qualifying what I’m about to say next :) …

If I had to choose one analogy to describe the state of publishing it would be a deer paralyzed in a beam of on-coming headlights. From numerous discussions at the annual ALPSP meeting, it became apparent that society publishers in particular are standing still in fear, unsure of which way to turn, or to make that risky move. From a high-level bit of questioning, it seemed many publishers didn’t have the right mix of people in their organizations for the digital world.

There was an interesting plenary session with Ziyad Marar (SAGE), Timo Hannay (Digital Science), Victor Henning (Mendeley/Elsevier), and Louise Russell (a publishing consultant). Ziyad and Timo seemed to have opposing perspectives on what a publisher today should be composed of or targeting. Ziyad was on the side of focusing on content, while TImo more on the side of focusing on the tech. That’s a simplification, and both of them probably value and implement both in their orgs, but the extreme views are the two sides of what I see in publishers today. Those who do not have people in place, either through empowerment or directly though titled positions, to make technology a center piece of their organization risk being stuck in the headlights.

I’ll be even more specific than technology, it’s user experience. We can all blame Apple for this one too. It may not be dominant over content just yet, but it’s coming, and those who do not have the tools and people in place will be left behind. This was missing in the organizations of many who I spoke with at ALPSP. And to do user experience right, you need to be focusing on the right technologies and the right product strategies, with the right people. I gave a high-level talk on cloud computing and many commented how they just didn’t have the people within the society to make it possible. That’s a mistake, not because cloud computing is the answer, but because you can’t then focus on building the tools needed to please the future reader, author, reviewer, etc.

What’s also interesting is that user experience isn’t something new to publishing, it’s been going on for 300 years. We think of publishers as just delivering content, but they’ve been tweaking the layout and typography of that content for centuries to make it more legible, more comprehensible, etc. That’s user experience. To make that happen today though requires people with different skill-sets than even a decade ago, and those people are either avoiding careers in publishing, not given priority, not empowered enough, or not even considered.

Before Pete (PeerJ co-founder) and I announced PeerJ in 2012 I related to him a little research that I had done on PLOS and lack of technology focus. This came about because we wanted people to know how PeerJ would be different than what had come before. I went through the WayBackMachine on the Internet Archive to look at PLOS’s website history. One thing stood out to me - it took several years before any tech-related people started to appear in the staff list and even today (like other publishers) tech empowered employees are not in positions of business strategy. I wanted PeerJ to make engineers equal to the editorial positions, and that’s how we’re different. That’s what’s needed if society publishers are going to continue.

Really, it isn’t tech versus content. They support each other, the only problem is that there are a lack of people in the position to make it happen today. Yesterday’s typographers are today’s user experience engineers, today’s human-computer interaction experts, today’s software engineers. That’s what scared me the most in all of my conversations at ALPSP, the missing people.

Business Insider’s CTO, Sheesh. Meanwhile I’ll no longer be reading BI.

That’s the question I’ve been trying to answer for myself over the last few months. One would think that without the UK’s Guardian newspaper slowly publishing new information on a weekly basis that we’d have already forgotten about the domestic spying, encryption disabling, etc from the NSA and GCHQ. It would have been news for a week and then turned over in a new cycle with more important headlines such as Mylie Cyrus and such.

For sure, the revelations from Snowden have caused more debate and action in the U.S. congress (both House and Senate) than Manning’s ever has (and in the UK’s parliament). And that’s something. But the amount of apathy from the general public is baffling. People are outraged, I know, but at the same time, we don’t seem to be doing much about it either - hence apathy. A lot of shouting, but little action. It’s really odd. Why aren’t we doing more? That’s the question I’ve been struggling to understand.

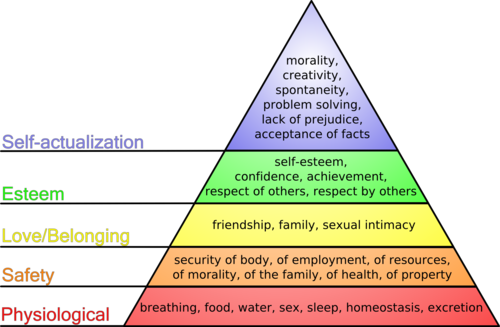

Lately I’ve been thinking about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in relation to this question (diagram above). There are a few caveats with the Maslow hierarchy (usually represented as a pyramid). The main caveat is that the needs can be fluid, i.e. some at the top may be at the bottom and vice versa depending on the location, culture, time, age, etc of the person. And to make this easier, I am categorizing all of the revelations that have come out from Snowden as privacy.

As best as I can tell, Maslow would have placed privacy into the highest need or “self-actualization.” The highest need, shown at the top of the pyramid in blue, represents only 2% of the general population according to Maslow (remember too the caveats above). Interestingly, Maslow also considered “self-actualization” to be the future of humanity, i.e. the best that we could become. Those at the top have a need for privacy, not because you’re hiding any thing in particular, but because you value it as an equal attribute to your creativity, your pursuit of intellect, and personal morality. In the strictest interpretation, those who don’t believe in privacy don’t believe in creativity, intellect, morality, ethics, etc either.

It’s a curious thing when someone says “innocent people don’t need to hide anything.” Or similarly, “the innocent have nothing to fear [about the privacy invasions].” Such statements come from people who actually haven’t achieved self-actualization for themselves yet. They’re further down the hierarchy is one interpretation. Another interpretation is that they believe all people should be held to a lower level of that pyramid; i.e. you should only be as high as the weakest link. What’s curious is that this is nothing new. We’ve been subjected to this for thousands of years from leadership in republics, monarchies, totalitarian regimes, all of them. No large populous government has truly sought to bring about the highest level of that pyramid.

If we were to measure government in terms of Maslow’s needs, it would fall into the second to lowest category of “safety.” In thousands of years of human civilization we haven’t really moved beyond that, which is another huge array of “whys” waiting to be answered. I think we see a glimpse of progression in the 4th amendment to the US Constitution (emphasis mine).

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

For many people, metadata, phone calls, Skype chats, email, Facebook messages, etc are an extension of their persons. If you are not free to do these things securely then you are unable to attain “self-actualization.” You are being deprived of achieving more. But still, why are we, as a populace, not more angry? Why are we not doing more to ensure this security of our persons? I think an answer, and there probably isn’t just one answer, is extremely complex.

In part, we can go back to Maslow’s assertion that only 2% of the population have reached self-actualization. If this is true, then only 2% of the population is concerned about privacy. Put another way, that means privacy is not the primary concern of the population. Remember again the caveats from above, that the needs are fluid and not binary. Everyone, to some degree, is probably concerned about privacy, but it’s not the primary need that they have. Looking at the list of needs in the pyramid above, things like food, shelter, jobs, love, friendship and others all come before privacy, intellectual pursuits, lack of prejudice, and creativity. And in fact, if you’re in power and want to change the debate, the easiest thing to do is to tell people (and remind them) that they need to go to war (Syria), that the economy still needs recovery, that marriage straight or gay (love in the hierarchy) is a more important debate than privacy. It keeps privacy out of the debate, and with limited privacy you have more power.

In effect, if 98% of the population doesn’t consider privacy amongst their primary needs then action will be limited. I actually think more than 2% of us are in the “self-actualization” part of the hierarchy. However, I think we’ve been deceiving ourselves about how filled those needs actually are. Once you fill the first two levels, it becomes more difficult to discern what the important things are (and again to each person there is fluidity in the needs). We are probably deceiving ourselves that access to Facebook, Google, television, etc are filling our needs higher up the hierarchy And if we’re deceived into thinking we’re filled, then a small thing like the removal of privacy becomes less of a concern. Or focusing the debate on any thing but a “self-actualization” need will mitigate that concern.

Imagine the reverse, where all you had were the first two levels filled, and only one thing at the top (the next three levels). How would you then feel if that one thing, for example privacy, were stripped away? You’d certainly notice it more than if you had basically every other need filled. Perhaps this is why people from countries that are worse off than the US/UK/Canada/Australia/etc, seem to take more action in the news. They’re barely at the second level of needs, sometimes at just the first level, and then they have things like democracy, freedom of expression, privacy (Zimbabwe, Syria, East Germany pre-1989, Somalia, etc) taken away. You had one thing available to you that represented the highest that humanity could achieve and it is taken away from you.

Right now we are being deprived of the highest that humanity has to offer. We should not be merely satisfied that in the West we’ve achieved the first two levels (and yes individuals in the West are suffering on levels 1-2 still). We shouldn’t be satisfied that this is the best our governments have to offer. We shouldn’t believe that we’re still needing to go to war after 10,000 years of civilization (a level-2 need). We shouldn’t be confusing comforts such as prime-time television and iPhones with our higher needs. I believe we can expect more and offer more to ourselves.

“You can’t have high quality and inexpensive (affordable) open access fees” - usually said in context of PeerJ.

I keep hearing variations of this from stakeholders in the publishing industry. Typically it’s coming from people with vested interests in maintaining the status quo, i.e. high margin subscription sales or high cost hybrid Open Access options.

Is this true some of time? Yes. Is it true all of the time? Not at all. One needs to look no further than the Japanese auto industry as evidence of this. Honda, Toyota, etc. All cheaper, and near universally better products than their American counterparts.

Being less expensive does not necessarily mean lower quality. It does suggest less greed, however. Value has nothing to do with cost.

Previously I had argued in “Science funding is borked” that we should be giving out many more and smaller grants, similar to the 500 startups approach.

Now in a new paper published in PLOS ONE and reported in Times Higher Education, it seems that this argument is starting to gain some data-driven support.

Here’s the PLOS ONE paper Big Science vs. Little Science: How Scientific Impact Scales with Funding

I’m a little baffled by the recent $35M funding round, which included Bill Gates, for social network for scientists ResearchGate. And of course the media baiting quote from RG that it wants to win a Nobel Prize for its efforts.

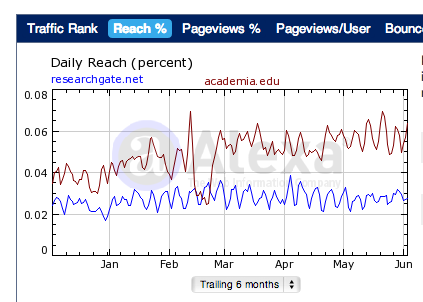

One look at the traffic stats tells you all you need to know as a potential investor. The graph below is from Alexa, which is known to undercount traffic, but it can be used to reliably compare competitors relative to each other. The redline is Academia.edu and the blue is ResearchGate over the past six months. Alexa ranks RG at the 5,433 most visited site, with Academia.edu at 2,686 most visited.

While RG claims to have 2.9M users, only a very tiny fraction of those are actives. Other traffic analytics stats confirm these numbers. My guess is roughly <5% at most are active each month (active meaning visit the site at least once). Then there is roughly the same amount of non-registered users visting the site per month. Are at most 145K registered users (+150K non users) visiting the site per month, with no revenue other than a small jobs board, worth $35M in funding? This probably values RG north of $150-200M. I must be missing something, or else Academia.edu should ask for $70M in its next funding round.

Then there is the value proposition. I fail to see any with RG. Academia.edu doesn’t have a lot either, but certainly more than RG. A lot of scientists have also compared Mendeley to RG and Academia.edu, which definitely has value proposition to users, and never raised such a round. One could also throw in FigShare, which has some overlapping functionality and more value add, yet it has never achieved anywhere near such funding to date.

Probably the biggest strike against such a large round however is researcher sentiment. I’ve yet to meet anyone exclaiming RG as beneficial to their work (quite the opposite in fact with many reports of spamming and site scraping). On the other hand, I hear plenty of scientists talking about the value of FigShare, Mendeley, Papers, and even Academia.edu to their work. One has to wonder what kind of due diligence was done by the investors here.

CHORUS is another attempt by subscription publishers to defeat Open Access. Probably no better writeup than Michael Eisen’s of how deceptive the intent and logic of this plan is.

CHORUS claims that it will save the US govt money if implemented, as part of the plan calls for the shuttling of PubMedCentral. The fallacy of course, is that costs to the govt (i.e. taxpayers) will actually INCREASE as publishers now have control of the “Open Access” content via a CrossRef like dispatching service. To maintain this dispatch service requires passing on the costs to their journal subscriptions — that ultimately means the libraries and agencies foot the bill.

If this is really going to save taxpayers money, then why have the publishers that are part of CHORUS not provided a cost break down? Let’s see the expected operating costs, charges to publishers to join this new organization, and the details of the API restrictions and practicality of retrieving the full-text for data mining. Then let’s compare that spreadsheet to the cost of running PubMedCentral. But that’s just the financial cost; more concerning is the cost of giving control of Open Access content to organizations whose business model is counter to the principles of OA.

Are these APIs truly open? What happens if I decide to build an aggregator with this content that is supposed to be Open Access? Will I be restricted or charged for high volume access, because publishers are now losing eyeballs as researchers go to my aggregator search engine? Do we really want publishers in charge of the key to the only source of all embargoed Open Access content? How gullible do they think the Obama Administration is?

CHORUS is a patronizing plan to researchers, libraries, and the American taxpayer. It’s a coordinated effort to sustain subscription-based publisher revenue streams and falsely paint PubMedCentral as a waste of taxpayer money. It is not about innovating on Open Access content and expanding its accessibility.

Just one more feather in the hat that the “serials crisis is NOT over.”

There’s an article on WIRED from last October outlining the similarities between 1950s auto prices and the private US health care business. In essence, the similarity is that consumers have no way of knowing what the goods and services they are paying for actually cost. For auto purchases, this was resolved in the 1950s when US Congress passed a law requiring auto dealers to place the manufacturer’s suggested retail price on the sticker. WIRED is now pointing to advocates who want the same for health care. Giant health care providers are charging wildly different costs for the same services to patients who have no way of knowing what the true costs are.

One cannot help but notice a similar “blind man’s bluff” happening in academic publishing. A recent Nature News feature tried to pin down some of those unknown publishing costs. And in an Oxford debate held a few weeks ago, Stephen Curry (Imperial College) pointed out that his own library was bound by an NDA to not disclose Elsevier’s contract details with other libraries. That of course is big publishing’s questionably legal practice to maintain the blind man’s bluff across universities. Prevent libraries from knowing what others pay (and thus estimating true costs) and you can continue to charge more.

As noted in the Nature News feature, the big 4 publishers partly justify this based on the complexity of their businesses that span more than just academic publishing. They say accounting for overheads that span multiple disparate business units is too complex to figure out how much is being spent on STM publishing alone. One finds this hard to believe and should probably give shareholders in those organizations a pause for concern. Either they truly don’t know their costs to publish, and thus can’t reliably run a sustainable business; or they just have never been pushed to release those numbers (as it would potentially lower revenues). Either way, it is fishy business that is arguably harming the consumer, just as it was prior to the 1950s auto sticker law.

Perhaps it is time that government demands publishers over a certain revenue threshold start revealing their true costs. Is it time for academic publishing to have its own “auto sticker?” The alternative is that we continue the blind walk in the dark.

I joined Mendeley as head of R&D at the start in early 2009 and left end of 2011. Here are my thoughts about my time there and why I eventually left to start PeerJ.

First, in terms of business success, regardless of your stance on Elsevier acquiring Mendeley, this was a win for the Mendeley team, so congratulations. I hear many saying that Elsevier overpaid (FT states £45M), but Elsevier is smart and they are getting a huge team in Mendeley that knows how to operate like a startup. That’s very near to impossible to grow organically with an established organization the size of Elsevier. This also gives Elsevier a major operational unit in London, which they did not have before. That and other factors say to me that the amount paid is about right give or take a few percentage points.

In terms of mission success, however, I am uncertain if this was a win. Mendeley had become known as the darling of openness, which in my view was already closing off when I left. Selling to Elsevier sets up a new challenge to maintain that open ethos, and unfortunately we can’t immediately gauge what the outcome will look like.

I joined Mendeley after abandoning my own fledgling online article manager and recommendation tool that I had started while still finishing up my doctorate. I started talking with the Mendeley founders in the Summer of 2008 just before they opened for a beta program. I was really impressed with their plans to “disrupt” the academic market then held by EndNote and also to allow wider discovery of the literature. At Mendeley I was responsible for building out new discovery tools with the data that we were collecting.

The R&D group did a lot in a few years (deduplicating 200M documents, real-time stats, search, Mendeley Suggest, etc), so I’ll mention just three of my projects below and what type of indication it creates about how Elsevier approaches things that are open.

One of my early projects was the “Open API.” It took some convincing at first to the founders that by releasing the extracted article data we would actually grow, but to their credit it didn’t take long for them to agree. I wrote the spec in late 2009 and worked with Ben Dowling (now an engineer at Facebook) to develop the first beta version of the API that was released in April 2010. After Ben left, Rosario jumped in to improve and expand the API and still heads it up in engineering. The API is now used internally at Mendeley for its own tools. From the start, the API was very controversial as we were now giving away metadata for free (titles, abstracts, etc) that publishers had always held onto tightly unless you were willing to pay for it.

Next up were “PDF previews” that display anywhere from 1-3 pages of a PDF on each of the article landing pages on Mendeley web. The inspiration here was the 30 second previews that iTunes gives (and now every other digital music provider). The thinking was that this would benefit publishers by sending them traffic that was ready to engage with their articles, something that only seeing the abstract can limit. And we were right, the data we saw showed that articles with previews sent more traffic to publishers than without previews. To many publishers however, this was even more controversial than the Open API, as we were now showing even more content, although you couldn’t get access to it via the API.

The third project was a JISC funded grant, DURA, that we co-wrote with Symplectic (now owned by Digital Science) and the University of Cambridge. The idea was to utilize the Mendeley Desktop client to connect to institutional repositories to allow drag & drop depositing. Put your authored papers into Mendeley and they are automatically deposited with your institution’s Green Open Access archive.

All three of these projects were impacted by Elsevier. With the PDF Previews out, Elsevier came out hard to limit what we could do. The Mendeley founders, citing little choice, cave to removing Elsevier abstracts from the API and taking down PDF previews of Elsevier articles. Meanwhile, another publisher, Springer, surprisingly took the opposite approach and wanted us to do more with the PDF previews.

With the JISC funded DURA project, I got word that behind closed doors Elsevier was allegedly trying to stop the project altogether at JISC. That project has since stalled since I left Mendeley.

These events were entirely against my personal open ethos and why I had originally agreed to join Mendeley. It was clear that the founders and I no longer agreed on the future (a blog post I had written calling out Elsevier’s actions was censored during the intense Elsevier talks) and tensions led me to reconsider my time there. It eventually came to a head and we agreed to part amicably.

If one is honest, from a business perspective the Mendeley founders did the right thing to comply with Elsevier’s demands. My personal passions about Open Access hindered that, so no surprise it didn’t work out for more than a few years. What I learned was that my next project had to have open at its core, rather than just tacked onto the side. For that reason then I co-founded PeerJ, an Open Access journal, with one aim of never being in the position to take shit ever again from a closed publisher.

I think that Mendeley as it stands today will continue to be useful even at Elsevier. That said, I think it will be challenging for Mendeley to become a truly transformative tool in science, which is what had originally convinced me to move from San Francisco to London four years ago. I cannot take all of the credit for the “open street-cred” Mendeley has gained over the years, but the projects I worked on had a big contribution to that and I can’t help to think that the day I left was the last day of further open innovation. It will be interesting to see what happens. I sincerely wish Jan, Paul, Victor and the team at Mendeley well.

Updated (10 April 2013): Let’s keep it classy Internet. Since I’ve witnessed some personal attacks against a few current Mendeley staff I thought I’d step in and state that there are still voices for change at Mendeley. I don’t want to leave anyone out, but since I saw attacks against them; three such people are William Gunn, Steve Dennis, and Ricardo Vidal. I know their character having worked together for years and know that they will do their best to make changes from within and wish them the best.

This is the latest paper, published in PLOS Genetics, from one of my former PhD advisors in graduate school.

This one isn’t even all that bad, from submission to publication took seven months. However, I didn’t have the heart to ask him if it had been submitted elsewhere and been rejected. I didn’t want to shit all over what is a great feeling to have another publication out the door.

Sadly, most papers do go through multiple rejections from other journals before finding a home. And that’s if they are not “scooped” while doing the long journal dance. This means that advances in research are tied up for 1-2 years in many cases.

Why I am upset and concerned

Delaying research helps no one. The paper above is an important one, that doesn’t immediately translate to saving lives, but is core basic research that one day could be applied as such. And this happens every day.

I cannot wait for PeerJ PrePrints to come out this Spring, which will put a stop to this nonsense.

It isn’t lost on me that what I am about to say is rather cliche and pronounced at least twice a month somewhere in the world. I feel that biological research isn’t progressing like it should be. First some background.

The two paragraph background

In circa 2000, about the time I was looking at grad schools, I read the book “Gene Dreams.” The book rehashes the biotech scene of the 1980’s and 90’s, along with all of the promises that biotech + gene therapy would bring to the world. It notes that all of those ‘dreams’ failed, but that the 2000’s would make it right. I was a believer! I entered graduate school determined to use gene and stem cell therapy to cure the entire F'ing planet. Spoiler alert, I failed.

I wasn’t alone though. Many others have failed in that pursuit as well. Gene and stem cell therapy is largely an 'applied science’ versus being a 'basic science’ (aka learning about the building blocks of what makes things tick). So, for a long time I felt that it was just applied science that had issues. The “issues” being that no solid or common frameworks to make discoveries or breakthroughs exist. And that it was better to do basic science if you wanted to succeed more easily. Years after completing grad school though, I think my bitterness was too narrow. I’m an equal opportunist, and would therefore like to bash basic science as well for lacking a modern toolset to take “it” (whatever “it” is) to the next level.

That’s the quick, slightly incoherent two paragraph background, now on to the (somewhat) present thinking.

I was at FooCamp last June 2012 and wound up in a session about biology (don’t remember the title). I think a discussion was brought up originally over the question of how programmers could get more involved with science in a DIY approach by Jesse Robbins. By this time, I had been several years removed from doing actual science on an actual bench with an actual pipette. Instead, I had taken up what I originally started out doing (at age 5) by programming shit; albeit shit related to science now.

Something that was said during that discussion brought me back to my graduate school days of failed experiment after failed experiment. Jesse asked, “Jason, how can I get more involved in science?”

My first reaction was, “Don’t! You’ll end up depressed.” All of those failed experiments, and all of the failed work by others in gene therapy, and most of the time we had no-f-ing-clue-why-they-were-failing. That was the biggest drain on me in grad school, not knowing why. Equally, if I did some kind of PCR directed-evolution experiment and found ONE good result amongst a thousand failed wells in a plate, my next step would be to toss those 999 failed wells and evolve the good well in another PCR round. How, stupid, was, I.

Having gotten back into programming after grad school, I immediately realized my error. Instead of concentrating on the one good well in a thousand, I should have taken the 999 bad wells to see why they went wrong. In programming, this is debugging by looking at your error logs, or similarly, test-driven development.

Moreover, what was missing was some sort of stack trace that would tell me exactly at which point the antibiotic I was testing started to kill the cell all the way up to the point of death (antibiotics were often used to test PCR evolved enzymes used in gene/cell therapy). It was then that I realized that not just applied science, but basic science was missing these “error logging” tools as well. We usually don’t know why experiments fail because 1) we hardly care about failures in science and 2) no one, AFAIK, has built the tools to examine the “why” stuff fails. Such an approach would be laughed at in programming.

Instead, in programming you check your error logs to figure out how to make things work as expected. And the reason we can do that is because someone in the past spent the time building error reporting tools. What is missing in biology (again, AFAIK) is a comprehensive set of error logging within cells.

This is why we’re in a progression slump; we can’t make the huge mental leaps in science because we’re now at the point where better tools are needed. This happens once a generation or so, where we’ve surpassed the infrastructure that was built by the previous generation. A more methodical approach within a framework is needed. A new respect for failed experiments is needed.

And I wouldn’t be surprised if building such error reporting within cells was more universal than we might expect at first, no matter what the cell type or species whence it came. Error reporting I suspect, much like DNA itself across species, could be generalized enough to require little modification per cell, protein interaction, or whatever. A common set of error messages could bubble up to a logging system to be investigated post-experiment. Even the act of building such error reporting would result in a giant number of new discoveries.

Of course, like any idea, good or bad, this has probably been “thunk” before, possibly at the same time. The thing is, I’ve yet to see anyone do it. Perhaps because they did and it failed, and so the research was tossed per usual.

Running a startup is difficult enough. Being a foreigner doing a startup is about 100x as difficult. The last thing you want to be worrying about is your Visa and not having a passport to do business.

I’ve lived in the UK for nearly four years now on a Tier 1 Visa. I moved here from San Francisco to join Mendeley as Head of R&D [note: left to found PeerJ before Elsevier moved in to buy them :)].

Last August I needed to send my Visa in for a two year extension. It has now been five months, and I still have not received my passport and new Visa. This is not an uncommon thing these days (read any Visa forum) for the UK Border Agency, the agency in charge of immigration decisions.

Obviously being without your passport is rather hampering as a co-founder of an Open Access tech/publishing startup with locations in both London and San Francisco. It’s outrageous actually, and the UKBA knows exactly what my business is.

I know for certain that I am not the only entrepreneur going through this. A shame, as startup companies are the ones bringing new investment to the UK economy and creating new jobs. And with the RCUK pushing for Open Access, you’d think there would be added incentive in this case. David Cameron is full of a lot of hot air, professing to be on the side of foreign entrepreneurs. From where I sit, we’ve received no help.

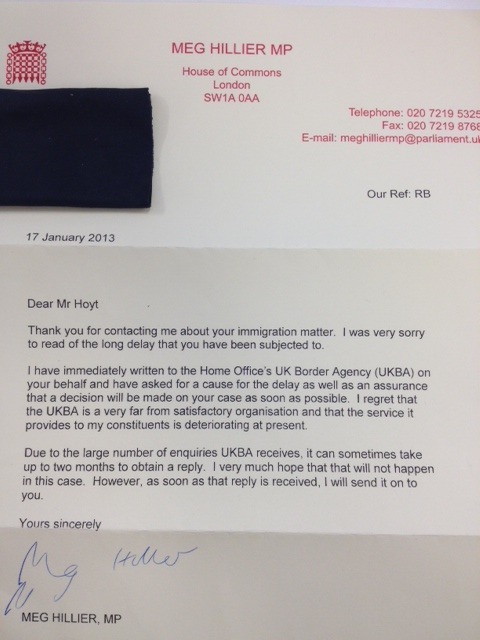

Finally, this week I decided to do something besides futile attempts at contacting the UKBA for information on the delay. I wrote to my local MP, labour party member Meg Hillier. And behold, a written reply within two days of my emailing.

“… I have immediately written to the Home Office’s UK Border Agency (UKBA) on your behalf and have asked for a cause for the delay as well as an assurance that a decision will be made on your case as soon as possible. I regret that the UKBA is a very far from satisfactory organisation and that the service it provides to my constituents is deteriorating at present. …”

- Meg Hillier MP - 17 January 2013, private correspondance (see image in this post)

Thank you Ms. Hillier.

Probably the most disturbing thing to me about the Aaron Swartz tragedy is this statement in 2011 from US Attorney Carmen Ortiz:

“Stealing is stealing whether you use a computer command or a crowbar, and whether you take documents, data or dollars.”

That is teaching our children that the law is always correct and that discretion should not be used when enforcing the law. It’s teaching our children not to question what they are being told by those in power. Had the American fore-fathers believed that “treason is treason” then the United States would have never had its Revolution and founding.

There is no physical law that governs the Universe that outlines stealing, killing, lying, etc. These are human fabrications to govern us as a society, tribe, and culture. We equally have the capacity to dictate when stealing isn’t stealing, or when an act of treason is the right thing to do as the American fore-founders discovered. That is how we advance as a civilization.

There is a tremendous difference between stealing for personal gain, and “stealing” [1] to release academic papers paid for with tax-payer money. A true leader would recognize that. It’s been reported that Carmen Ortiz had political ambitions to one day run as Governor of Massachusetts. Is that the kind of leader a state would want? A false leader who doesn’t recognize when an act has morally justified grounds? A real leader would act to make changes, not throw the book at someone.

MIT should be ashamed as well, whether they were actively pressing charges or passively standing by [reports are conflicted over this]. MIT as well is supposed to be leading us. In the past they were one of the first universities to offer free and open classroom lessons online. Here, they failed miserably to lead by example that academic research should be made open.

The Aaron Swartz story is bigger than just a 26 year-old doing some computer hijinks and getting bent-over by those in a position of power. It’s even bigger than the importance of Open Access to academic research. It’s surfacing some major issues that we have in society in both the U.S. and beyond about true leadership [note: I am a US citizen currently residing in London, UK]. Ortiz was put into a position to use her discretion. Instead, she let her ambitions dictate Aaron’s fate.

At the end of the day, if it is against the law to steal whether morally motivated or not, then you’ve broken the law. Laws can be changed though. New countries can be formed. And leaders in power can use their discretion to apply fair judgment, not to further their own ambitions. Where have all the true leaders gone?

footnote

1. Note that Aaron wasn’t even technically stealing in terms of the law, at most it was breach of contract [according to several reports].

This morning, by way of @SimonBayly, I came across the article “Towards fairer capitalism: let’s burst the 1% bubble” in yesterday’s Guardian.

There’s a nice late 1800s/early 1900s quote that I can’t help but correlate with today’s academic publishers:

“The barbarous gold barons do not find the gold, they do not mine the gold, they do not mill the gold, but by some weird alchemy all the gold belongs to them.”

- Haywood, William D. The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood. New York: International Publishers, 1929, p. 171

What this is saying, and the thesis of the Guardian article, is that the gold barons of the 19th Century and the financial bankers of the 21st century are wealth extractors, rather than wealth creators.

The Guardian thesis goes on:

Value creation is about reinvesting profits into areas that create new goods and services, and allow existing goods to be produced with higher quality and lower cost.

Think about that. When was the last time we saw academic journals lower their prices? Subscription-based (and in cases even Open Access based) academic publishing is the opposite of value creation, it is value extraction.

The byproduct of innovation of the Internet has turned a wealth creating industry of academic publishing into a wealth extracting one. Make no mistake, today’s publishing executives are equal to yesterday’s gold barons and hedge fund managers. The Internet has given publishers the opportunity to lower prices, but they’ve chosen to do the opposite. That’s value extracted from scientists.

An important aspect of the Guardian thesis on economics isn’t that profits are inherently bad, but that they need to be reinvested to create more value.

I’d like to think this is what we are trying to do at PeerJ by creating value for the community. We made the price ridiculous at $99 for lifetime publishing. You’re forced to innovate with a price tag like $99. What’s more, we’re experimenting with free publishing as well with PrePrints (non peer-reviewed and non-typeset academic articles).

The thing is, we don’t know what the right price is for academic publishing today [1]. I don’t think it is what subscription journals have been charging, or most Open Access journals have been charging for that matter either. I suppose the thesis, of hedge fund managers and academic publishers robbing value, shall be proven if PeerJ continues to survive.

If you’re not lowering your prices then you’re not innovating. And if you’re not innovating, then you’re not creating value.

Footnotes:

1. It’s definitely not free, as it costs money to run servers and pay staff who maintain those servers, etc. ArXiv (non peer-reviewed) is a good example of what the right price might be, though even they have substantial costs that need support.

If it weren’t for Aaron’s heroic actions to release academic research articles in 2011, I am unsure if PeerJ would have ever been born.

Today’s news was shocking. Aaron Swartz was found dead from apparent suicide on the 11th of January, 2013 at the age of just 26. For the science community and Open Access advocates, Aaron was the man responsible for the (near) liberation of all pay-walled JSTOR content in mid 2011. He also co-wrote the first RSS 1.0 specification at the age of 14 and led the early development of Reddit.

JSTOR and MIT eventually dropped the civil case against him (publicly anyway), but the U.S. government continued criminal proceedings against him. JSTOR, it should be noted, was not his first attempt at freeing information. Aaron was facing up to 35 years in prison for the act of setting academic research free. It’s unknown if this was the reason for his suicide, but that’s not why I am writing.

The events around JSTOR and Aaron’s prosecution were probably the final straw for me. What kind of world do we live in, where such harsh punishment is sought for liberators of publicly funded information? The indictment of Aaron and the severity of the probable punishment angered me.

I wrote the following in July 2011 after learning about Aaron’s fate:

Will the JSTOR/PirateBay news be Academic Publishing’s Napster moment? i.e. end of the paywall era in favor of new biz models?

Something had to be done. I wanted to turn Aaron’s technically illegal, but moral, act into something that could not be so easily thwarted by incumbent publishers, agendas or governments. Over the next few months I let that desire build up inside, until one day the answer came in the Fall of 2011.

It was then that the groundwork for PeerJ was first laid; a new way to cheaply publish primary academic research and let others read it for free. Aaron was significantly responsible for inspiring the birth of PeerJ and what I do now trying to make research freely available to anyone who wants it.

I hope that when the history books are written in decades time, that Open Access crusaders like Aaron will still be remembered. My thoughts go out to Aaron’s friends and family. Know that Aaron’s light and efforts will live on. Thank you, Aaron, for inspiring us.

Good discussion going on over at Ross Mounce’s blog on which publishers are using XMP and why it is a good thing.

How often do we hear this, “We’ve just raised a small seed round and are using it see if we can gain product-market fit.”? In other words, they’re spending time and money without any inclination that there is a market available. I’ve not done the research, but at what point in history did this become a good strategy for the founders involved? The odds of success are tiny.

Building a startup with a huge market available to it is hard enough. Building a startup and trying to create its own market is a disaster waiting to happen. Far too often, I see startups trying to do the latter. You are wasting your time if you don’t start with an idea that has product-market fit from day one.

I’ve often heard people say that Apple created an entirely new market when it introduced the iPad. Same with the iPhone when the app store was launched. This isn’t true though. The ‘market’ already existed, it was the media/entertainment market. The iPad was just another device to leverage that market. Apple knew what it was doing.

I mention Apple, because they are a good example, for this specific case, in knowing your product-market fit before you even begin. For startup companies that manage to raise a small seed round (<$500K) it means you’ve been given a chance to demonstrate that product-market fit. For the Angel(s) involved, that’s great if you go on to prove that, and if not, well, they’ve invested in enough startups to hedge their losses. For >95% of startups though, you will never achieve that product-market fit if you don’t already have it from the start.

The best way to tell if your idea/startup has product-market fit is to ask yourself what other companies are successful and doing what you are thinking of doing. By success, I don’t mean raised a round (or even multiple rounds), I mean profitable and a staple in a large portion of people’s lives. If you can’t name several companies in your area, then 1) you don’t have enough knowledge of your area or 2) your idea doesn’t have an audience.

Unless you are trying to find out who the best actor might be that is. It’s like saying, “they just won the ‘Presidential debate,’ therefore they must be an awesome President.”

There is absolutely no correlation between the ability to deliver a pitch and the ability to successfully run a business.

What has spurred this bit of a rant is a blog post I woke up to this morning about the Founder’s Institute training their “student entrepreneur’s” on the fine art of pitching. Basically every incubator does this, so FI isn’t alone. And they do it for a reason, because this is what investors expect when you sit down with them, a well-polished pitch. And to be fair, investors usually don’t throw down money just because of a pitch, there is a lot more due diligence, usually.

I think that last point though, further due diligence, further backs up my claim that startup pitch contests do not actually determine the best business opportunity. They determine the best pitch, and that is all. In fact, winning a pitch contest might actually be harmful to your company, because it can bring a false sense of success; that you’ve achieved 'product-to-market fit.’ It will certainly raise the level of your profile for a short-while, but I don’t believe there are any self-fulfilling prophecies when it comes to becoming a successful business.

[Note: the irony of me writing this post is that at this very moment I have a nine month old getting fussy directly into my ear. My partner is starting to give me the stink eye as well. I hope she doesn’t read this.]

I was lucky enough to be invited to FooCamp earlier this year. Imagine a 2.5 day weekend spent with about 200 tech people that are 10x more accomplished and brainiac than you, and that’s FooCamp. Oh, and we sleep in tents and make our session agendas. It was awesomesauce.

I went in fully expecting to be immersed in a world of tech. And that was certainly true. There were two sessions however, completely unrelated to tech, that really stood out for me. One of those was put forth and led by a fellow entrepreneur who was about to become a father for the first time. He was calling for advice from any other fathers attending. For all of us “been there, done that” fathers the advice was nothing new. No one went into what it was like to run a startup at the same time as having a baby, but some general work/life balance was discussed. I’ll save my thoughts on how to [try and] achieve that balance for a future post. My personal take-away was that being a dad is a huge asset to a new company, rather than a limitation.

To be clear, it is not that I felt the opposite before that session, but it certainly helped to verify some of my previous assumptions by having more data points. Whether a correct assertion or not, I’ve always felt that there was a slight stigma in Silicon Valley that you can’t be as effective as a founder if you are a dad. The perception is that you need to be spending all waking hours devoted to the company. Whenever I find myself not doing something startup-related, I envision that scene from “The Social Network” in which Sean Parker yells at Dustin Moskovitz to get back to work after he takes his eyes off of his computer monitor for 5 seconds in the Palo Alto Facebook house. In essence, the perception is that parents are more of a liability than an asset. Is this true though?

It’s true that if I were single then I would definitely be able to devote more time to nothing but work. We could debate whether those extra hours would be as effective (i.e. are there diminishing returns or not). I won’t go there though. Instead, I’ll propose that given a hypothetical of a parent and non-parent working the same number of hours, that the parent will have a greater impact.

[Aside: When I went with my co-founder to pitch investors, I was fully prepared to explain that I was a father and why it wouldn’t be issue. It never came up, but if it had, I know that our own investors would be fully supportive.]

So, back to that hypothetical then. I’ve been a father for eight years now, and without a doubt, it has made me a much more effective manager in the office. Being able to effectively manage projects, competing interests, and people is the number one asset, other than vision, that a startup founder can bring. Indeed, more startups are founded by people in their 30s (more in mid-late 30s), than any other age group [Here’s a list of some of the more well-known startups founded by 30+ year-olds]. I’d also hazard a guess that many of these are also fathers; many I know for a fact who are.

No offense to the non-parents out there, or founders in their early 20s, but effective management only comes with experience. So, unless you’ve been in a managerial role for years, or happen to be a parent, you are going to be less effective in some aspects of your business. What I wish I had known before FooCamp, was that I was not alone. That many startup founders are parents. This is why I felt the urge to write about the topic, so that other parents, who equally feel that stigma, will stop questioning themselves. It’s an asset to be a parent.

There are many other assets besides management that I’ve discovered help me just because of being a parent. Rather than go on though, I’d like to hear from others. So go ahead and make a comment. And if any other startup parents are in London then I’d love to meet up and do some parent hacking together.

Ahhh, and he’s down for a nap finally! Up since 5am on a Sunday :(

@pgroth pointed me to this blog post from a recent post-doc now turned research group leader. Fact is, careers outside of academia are now the norm and majority, rather than “alternative.”

Michael Jordan, arguably the greatest basketball player yet. His son? Not so much. Wayne Gretsky, also arguably one of the greatest hockey players ever. His father? Not so much. The list of superstar athletes goes on. Similarly, children of the world’s tallest people are never as tall as their parents. What’s going on here?

It’s a well known statistical ‘rule’ known as regression toward the mean. In any sampling with extreme outliers, a second measurement will not have such extreme outliers. It happens throughout nature and is also visible athletics. Though less proven, it is also visible in business and in culture.